A last look at Ceuta – every town in these parts seems to have an ancient fort on top!

A last look at Ceuta – every town in these parts seems to have an ancient fort on top!

As predicted, this leg was a little unpredictable.

On March 7th, after poring over tide charts for literally hours, we left Ceuta and at times were managing only one knot over the bottom. The wind was light and it should have been the beginning of the favourable current, but somehow we had at least three knots against us. I’m still not sure what was going on there. Gauging the tide is more difficult than it seems in the Straits of Gibraltar because the distance from shore changes the current quite significantly. For example the middle of the channel is always flowing into the Mediterranean even on a falling tide, while more coastal areas vary. This is one place where local knowledge would make all the difference, and we didn’t have any.

Eventually things turned in our favour current wise, but the ships! Every ship entering or exiting the Med has to go through this gap and some were actually waiting their turn, drifting sideways, while others were steaming through. In the dark and even with the AIS transceiver which gives us course, speed and proximity of each of them it was a little nervous-making, but we managed to keep our distance. We contacted one or two just to be sure that we were seen.

Sun up on day one of this leg brought a very pleasant, sunny day but little wind and a lot of motoring. It was now clear that we were simply not going to get the wind we want. As if to underline that point it rose steadily from the south, right where we were trying to go, and once again blew at over 30 knots off and on until about midnight.

The Lonely Sea and the Sky

I’m getting tired of this 30 plus knot business. Truth be told, now that it’s over, in my last blog I wrote that “We arrived (at Ceuta) in really fierce wind and waves . . .” That was mid day and not too scary but that night Sylvain asked me how hard I thought it had been blowing. I said I’d seen the wind indicator hit 38 knots but thought it had gotten up to the 40s. He had been steering and keeping a closer eye on the wind speeds. He smiled politely and said the highest he saw the wind indicator go was to 58 knots! That’s something a good captain tells his crew not at the time, but over a beer later when we’re tied up to something that includes cement.

The ships were thinning out but Alex and I had a near miss at about 3 am which was very strange. A smallish ship of about 250 feet or so was closing with us as we were going in the same direction and we tried, in vain, to get him on the radio. We tried too long as it turned out, hoping to avoid having to tack, and when it became clear that he wasn’t communicative, or changing course, the wind suddenly dropped and we didn’t have enough speed to go about. Alex started the engine, something we were hoping to avoid because Sylvain was asleep, and gunned the engine off to the east to get the hell out of his way. That little rush of adrenaline certainly helped us stay awake for the rest of the watch.

A few times we have had unresponsive ships. In fact one time two weeks or so before when we couldn’t raise one we heard another ship running parallel to us also try calling on our behalf – “Calling (the name of the ship). Do you see the sailing vessel in front of you?” No response. Whether the bridge watch on these ships just don’t want to bother answering or have gone for coffee or are fast asleep I have no idea. Sylvain says that in his experience they are nearly always watching out for us and very accommodating and helpful. But you can’t count on them all.

By mid-morning on the 8th it had calmed down to a reasonable 15 knot wind but still from ahead. All the banging about had made me feel a little sick, which was frustrating, and then we got news that yet another low was forming. The next day, (at least it was during the day) was still another day of 30 knot plus winds and the boat bouncing all over the place. We actually chose to sail west, more or less into it, because we figured that would put us in a good position to head south after it was over with strong but manageable wind. Heading toward the coast of Africa would be more comfortable, but leave us with very little wind. That was a tough day, March 9th, by this time feeling soggy and damp and unable to do anything much except keep the boat on course. For someone like me who likes to accomplish things during the day, the time wasted just sitting and waiting for the weather to improve was tough. And being sick doesn’t help. My question is, why do all those sailing posters show casually clad, bronzed bodies and smiling faces while we’re dressed in long underwear, two sweaters and full wetsuits? And we’re not smiling! But the day did pass, the weather calmed down as forecast, and Alexandre served up an interesting concoction of couscous and vegetables which somehow settled my stomach once and for all. By the time I struggled out of bed late the next day we were under full sail in 15 – 20 knots and making 7 knots with 300 miles to go. It was a little closer to those sailing posters.

We even got the spinnaker up in the evening but the wind dropped and we motored all night. At least that engine power provided hot water – we all took showers – and then the night watch was quiet with a million stars.

With daylight there were a couple of visits from real crowds of dolphins frolicking around us and on we went in calmer waters. It actually looked like we’d finish with a nice, yachtsie spinnaker run right into Los Palmas on Grand Canary Island but alas, the wind dropped yet again and the last 10 miles were motor-sailing.

The first of the Canary Islands

Grand Canary Island

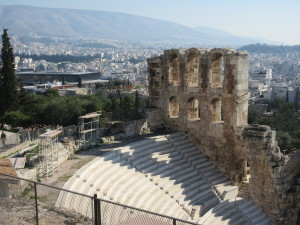

But what a location!

The marina in Los Palmas holds about 1300 boats ranging from runabouts to super yachts. There was even a Swedish ketch of about 150 feet with “Sailing for Jesus” painted on the side. While the marina had said they were full they did manage to find us a slip and we were able to tie up, fuel up, and then sit down and have a minor booze-up! Numa and Sarah who had their sloop “Squall” in Tadoussac for the last half dozen years are here, it turns out. They came over for a visit and we all went out to dinner together. They left last July for the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Cape Breton, the Azores and other islands before landing at one of the other Canary Islands and, for the last month, being located here.

Great views from the high end of the city of Los Palmas

It is interesting to see the so-called “blue water” sailing crowd from this angle. There are a lot of 30 to 50 foot sailboats with people living aboard indefinitely. They are mostly couples but often there are children as well. In the marina many are working on their boats. There is a motor’s marine manifold on the dock, an auto helm being disassembled, a wooden cupboard removed from another boat, wiring work being done, broken blocks and pulleys being replaced, someone up a mast fixing an aerial or a halyard or a fitting. They need to be knowledgeable about their boats’ needs and it is impressive to see the exacting demands they place on their equipment. It is never a question of a repair being “good enough for now.” It is either right or it is wrong. And nobody wants to go to sea with something wrong.

And patience. “When are you leaving?” is a question answered very often with an in depth review of the weather systems in the area and a possible window to leave if things don’t change too much. Where in Cartagena we saw a 24 hour window to scoot out before the low got worse, others were waiting till the whole system was through – maybe a week – and would carry on their way after that. It’s no good setting arrival times, (as we have learned, not even departure times) because weather and equipment dictate the possibilities and they can both provide surprises. While at the Canaries I remembered that when we stopped in Cartagena they had said there was a storm at the Canary Islands that had rerouted a big cruise ship. I asked Sarah about that and she said several small boats, and a freighter, had been sunk in the storm. That sort of story provides plenty of incentive to err on the side of caution.

A busy Harbour

And speaking of time, time is what has checked out for me. The delay in Patras was simply too much. By the numbers we took 3 days to get from Patras to Italy, 13 to get to Ceuta and another 7 to the Canaries. We stopped for 2 days of repair in Italy, and another 3 days waiting for weather in Cartagena, Al-Hoceima, and Ceuta. And there have been 7 days, nights, or parts thereof when the wind has blown harder than 30 knots consistently. But before all that there were 42 days in Patras getting the boat ready and waiting interminably for clearance to leave. I have had a family holiday in California planned since before this trip, and family comes first. There’s no way Chelona and her crew will be in the Caribbean in time for it, so this crew-member is jumping ship. Luckily Alex’s conjoint, Sarah, and Martin who likewise got timed out when he joined us in Patras, are signing on for the next leg. Lots of brains and muscle to support Sylvain and Alex on the Atlantic crossing.

I can’t say enough about Sylvain and Alexandre. Sylvain is the most capable sailor I’ve ever been with and very careful in his handling of the boat. He loves it, obviously, and is very good at it. Alexandre is Mr. Meticulous about all things, figuring out every component in the boat and gathering information about everything he needs to know. He’s also a chef extraordinaire, who provided great meals in difficult conditions at all times of the day and night. Together with Sylvain’s famous egg and fried potato and onion and I don’t know what all breakfasts, we stayed very well fed. You couldn’t ask for more pleasant or patient ship-mates. They’ve made it possible for this old guy to be a part of this voyage and I’m thankful to them.

Much as I have always wanted to sail across an ocean, that dream has faded after this experience. I have now seen enough ocean cruising for my life-time and will cheerfully return to my lovely little antique boat, my sailing dinghies, and my coastal cruising and day-sailing. This life is not, and never has been, for me. It is wonderful to have seen it first hand and the memories, good and bad, I’m sure are indelible. I’ve learned a great deal about boats and sailing, about travel and the sea, and about myself. It has been a privilege to have had this opportunity and I’m glad I took it, but I leave with a tremendous respect for the people who adopt this life-style. It is hard work. It can be expensive. It demands a lot of thought and planning and flexibility. The hardest part for me has been the separation from family and friends and particularly from Jane. She has coped with a heavy winter in Tadoussac by herself in my absence, and stage-managed the life I left behind, keeping me up to date on whatever I needed to know. I know you’re never supposed to say never, but my blue water sailing days are done, and I will never separate myself from Jane again for such a long period, till death do us part.

The crew going forward – Sylvain Martin, Sarah and Alexandre

Thanks for your interest in following this trip. It’s been a much anticipated high point for me to come ashore each place, get to a wifi café, and catch up on my e-mails. I really appreciate the interest, but I can’t wait to return to my real life in Tadoussac with Jane.